When Indy 500 Tradition Has A Real Price

On the same day that IndyCar announced a return to a higher performance era with an engine formula with horsepower similar to the series’ hayday in the early 1990s, another old friend returned – the drama of “Bump” Day.

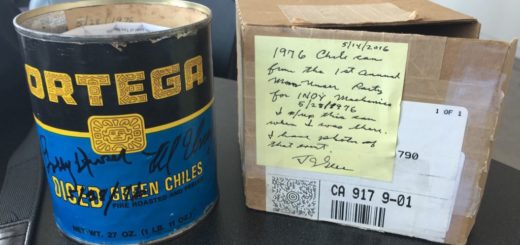

For those new to racing, big entry lists of cars and drivers looking to compete in the Indianapolis 500 are commonplace in the history of the race. (For example, for the 1984 race where 117 total cars were entered and 77 of them saw any kind of practice time).

The starting spots for the race are set through qualifying, where drivers take 4 laps around the 2.5 mile Indianapolis Motor Speedway, and the fastest average time sets the field. A long-standing tradition dictates that the field is set at 33 cars – and if you aren’t among that 33, you get sent home. Bump Day is the day when the drivers that will be in the Indianapolis 500 field is determined, If the field is full at 33 cars, and someone faster comes along than the cars in that 33, the slowest drivers get “bumped” out. (Ironically enough in 1984, rain meant that no one actually got bumped from the field). Until very recent years, qualifying drama and bumping was woven into the fabric of the Indianapolis 500 experience.

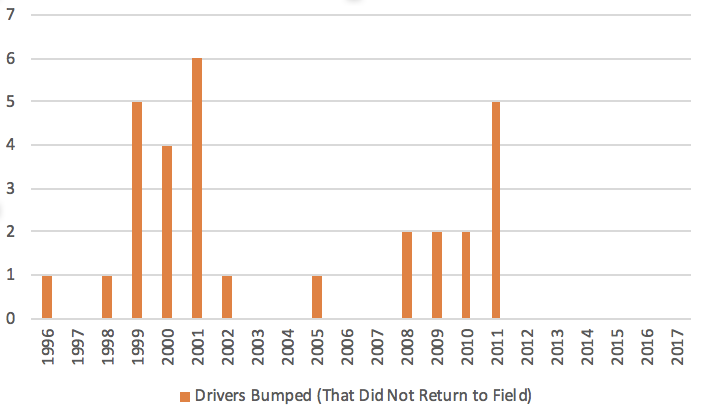

Consider 1993, when defending IndyCar Champion and 1986 Indy 500 winner Bobby Rahal got bumped in the last minutes of qualifying, and nearly bumped again in 1994.

Also, 2011, when more than 40 cars attempted to enter, and the drivers of then Andretti-Green Racing, had to resort to bumping each other out of the race.

And, of course, long time IndyCar fans will remember the absolute shock when Team Penske did not make the 1995 Indianapolis 500, a year after building a custom super high-horsepower engine that blew away the field. (The engine was called the Beast, and is the subject of an excellent book by Jade Gurss of the same name, if you want to learn more about the development process of this engine). Imagine baseball without the New York Yankees, and you get an idea of how big this was.

In 2018, the ghost of Bump Days past struck again as two popular drivers, James Hinchcliffe and Pippa Mann, got sent home after the first Bump Day that provided real drama since 2011.

Hinchcliffe, a former pole winner who nearly lost his life at Indianapolis in 2015, has become the face of a major Honda campaign in the United States and Canada and one of the most recognizable drivers to the general public from his Dancing With the Stars run. He’s said before that “Indy is a cruel mistress sometimes”, and no one in recent times had experienced more of the highs and lows of the 500.

Mann, who gives her time tirelessly to various charitable causes and the Community, had her annual one-off drive with Dale Coyne Racing, but with an extremely limited budget, and extremely limited track time, couldn’t get her car fast enough to make the race.

So, they both got sent home.

The visceral rotation is, sometimes, Indianapolis doesn’t care about resumes, doesn’t care about hard work, and is cruelly unfair. That’s part of the reason that being able to run in the Indy 500 actually means something beyond a potentially healthy paycheck. That’s why it matters to be an “Indy 500 Participant” and even in the more exclusive club of “Indy 500 Champion”. That’s tradition. And few sporting events adopt tradition more than the Indy 500.

But is it really that simple?

The counterpoint, like so many other things in modern sport, is the reality of the economics of racing.

In early 1990s, the budgets from tobacco and alcohol brands provided millions of dollars of funding that propped up the series. Indeed, both Rahal (Miller Beer) and Penske (Marlboro)’s primary budget was provided by these brands during the year of their Bumps. Tobacco, specifically, invented hundreds of millions of dollars in racing when industry ads were banned in the 1970s. Even Team Penske’s 20-year association with Marlboro ended in 2010.

In short, sponsorship in IndyCar is hard. Real hard. A full-year budget for an IndyCar can cost $5-8 million, and an Indy 500 only package can still be $1 million or more. That’s a lot of sponsors who have to foot the bill, and they have high expectations for their money, which often include appearances in the most marquee of races – the Indy 500.

This commercialism of racing has provided a less than popular “fail-safe” option of having teams buy ride or replace drivers in safely qualified cars. This option has been a controversial, but sometimes necessary choice for sponsors.

In 1992, Scott Goodyear replaced driver of a second team car Mike Groff, started 33rd, due to sponsor commitments and finished 2nd in the closest finish ever.

In 2011, Michael Andretti’s decision to buy a ride for Ryan Hunter-Reay from A.J. Foyt likely saved jobs for his team as DHL, the team’s primary sponsor required an Indy appearance as part of their sponsorship contract. In fact, the original driver of that car, Bruno Junqueira had the same fate happen to him two years before.

Presented these options, what did this mean for Hinchcliffe and Mann? Tradition had a hard monetary cost, and presented a moral dilemma. Buy your way into the race? Or potentially disappoint your sponsors?

In days after the Bumps, it became clear just how much would it cost to get a ride. Car owner Dale Coyne suggested it would be about $2 million. Hinchcliffe’s teammate, and possible replacement candidate Jack Harvey wouldn’t do it at any price. Conor Daly suggested “life-changing” money.

After nearly a week of debating his options, Hinchcliffe today decided to sit the race out, and by most estimates has handled the situation with grace and dignity.

Pippa, who is often open, honest and extremely transparent about her challenges in funding her annual ride in social media, shared her thoughts today in a heartfelt post to her fans. It still hurts.

The Indy 500 is steeped in annual traditions. It’s a race filled with drama, joy, heartbreak and triumph. This is why race fans love it, and why the 102nd race will be run on Sunday. Longevity matters.

But depending on who you are, tradition may have just cost too much this year. Or, may matter more than anything.